Once the site was established, growth was rapid. A second blast furnace was added in 1876. By 1879 the company reported annual outputs around 60,000 tons of coal and 25,000 tons of iron ore. Determined to become self-sufficient, management developed supporting facilities, ultimately reducing delays and their reliance on imports. By the 1880s the plant moved from iron to steel, installing six open‑hearth furnaces and switching railway material production accordingly.

John Hughes died in June 1889 while on business in St Petersburg. Control passed to his sons: John James became managing director and lived largely in St Petersburg; Arthur David and Ivor Edward alternated the resident directorship; Albert Llewellyn managed the analytical laboratories and blast furnaces. Under the brothers the 1890s saw major expansion. Two new furnaces were built and others remodelled; output tripled, and recognition followed: a gold medal at the 1882 All‑Russia Exhibition in Moscow; a State Emblem at Nizhny Novgorod in 1896; and the Grand Prix—the highest award—at the Paris World Exhibition in 1900.

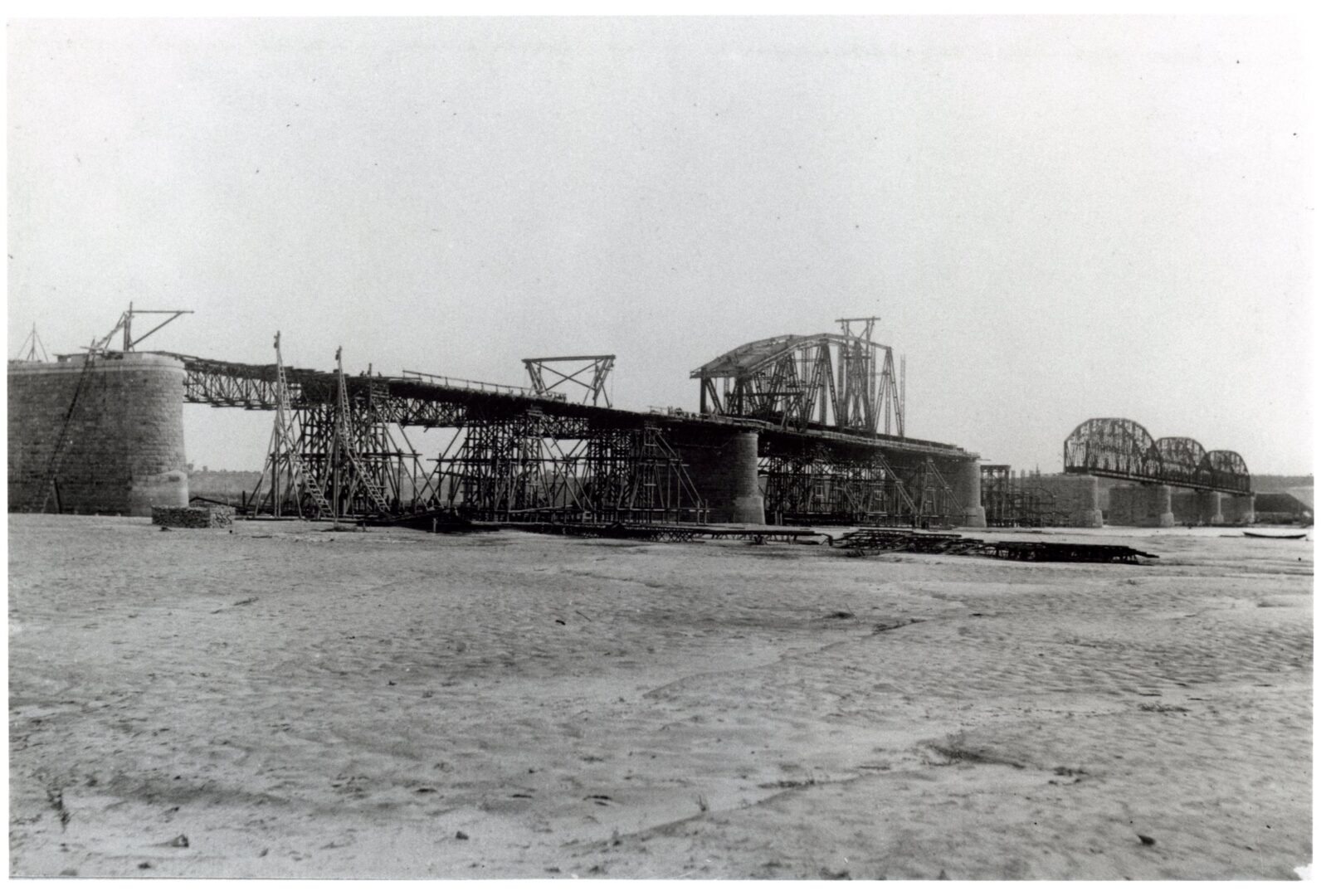

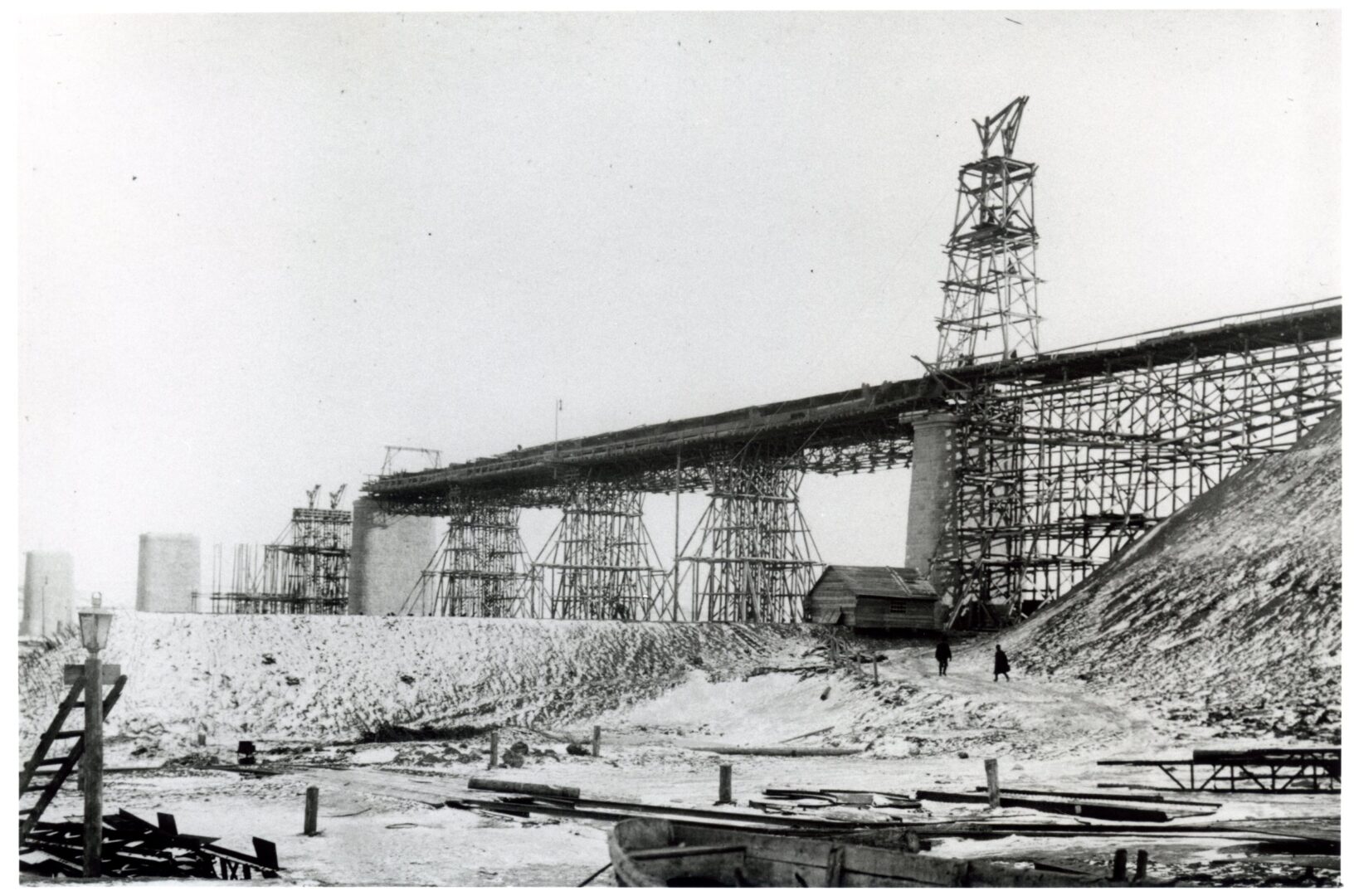

The turn of the century brought obstacles: trade contracted, the Russo‑Japanese War (1904–05) and the 1905 First Russian Revolution unsettled markets and labour. Yet by 1910 the company had diversified into constructing large steel bridge sections. During the First World War it added a plant to make artillery shells, fulfilling one of the government’s original hopes when the venture began: that Hughes’s works would strengthen Russia’s strategic industrial base in times of conflict.