The first workers and managers went by sea, following the plant equipment: through the Mediterranean, across the Black Sea, into the Sea of Azov, landing at Taganrog and then by ox‑drawn transport over roughly a hundred kilometres of open steppe. Sailing could be slow and hazardous, and therefore as the European rail network grew the train became the preferred route.

A common rail journey began at Holborn Viaduct in London and ran to Queenborough, Kent; from there travellers crossed the Channel to Flushing (Vlissingen) in the Netherlands. The route continued through Hanover and Berlin, then eastwards to Warsaw, Brest, Kiev and Kharkov before reaching Hughesovka. Surviving postcards from John William Jones, a colliery engineer from Hengoed who worked in the town, trace the stops in reassuring detail to his family in Glamorgan.

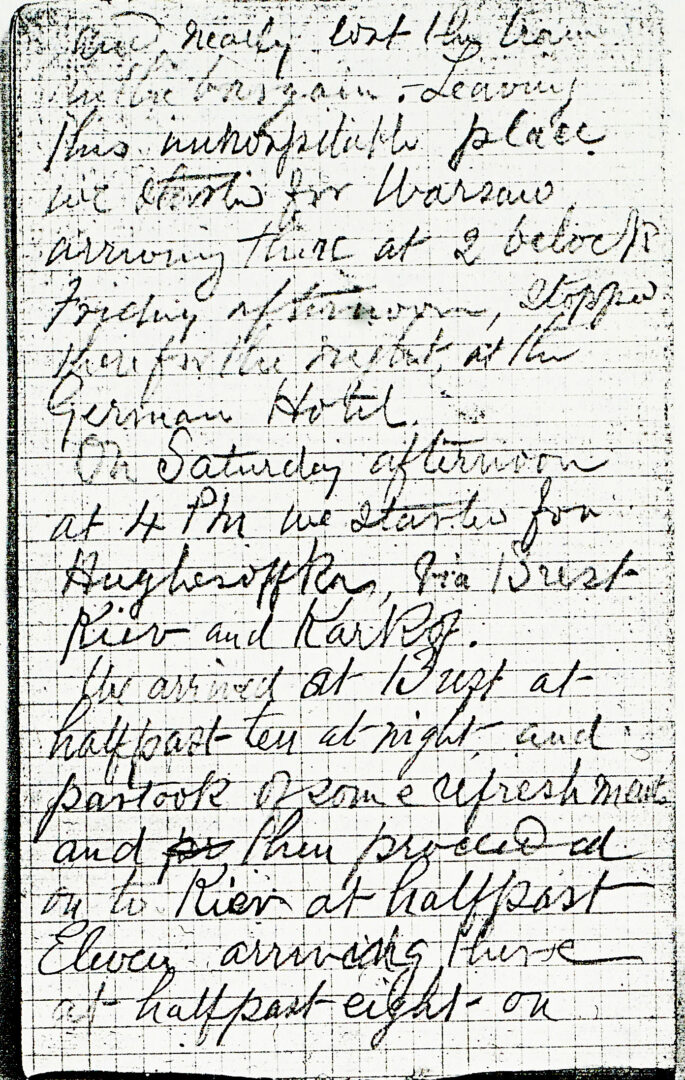

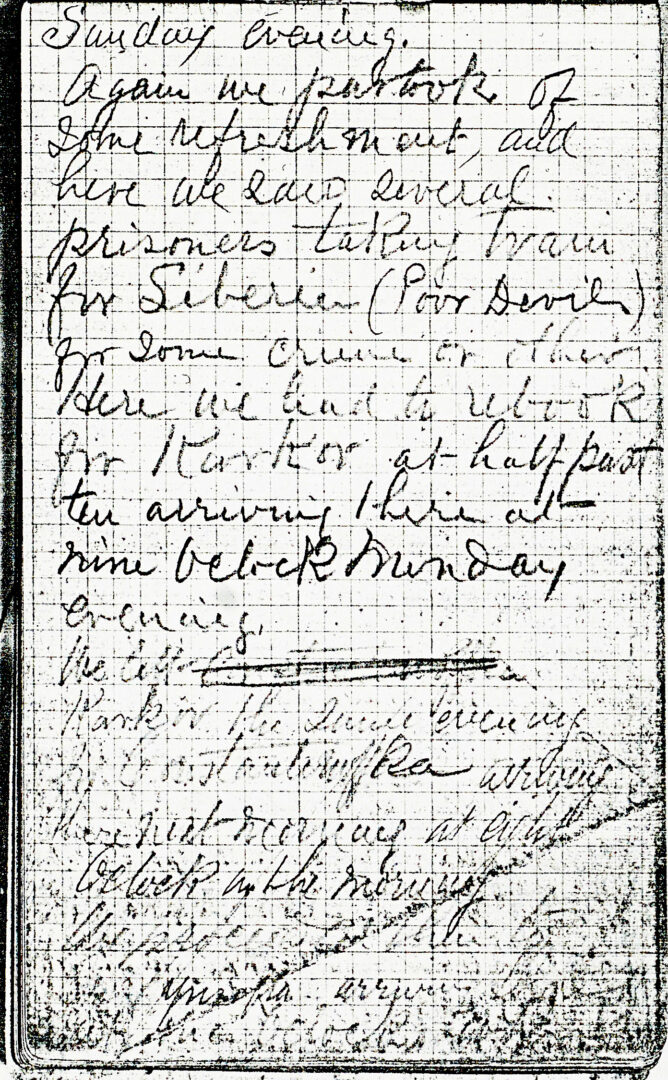

Letters and diaries capture the experience of travel. Edward Davies Watkins noted repeated bag checks and a surprising variety of refreshments across borders, and admired the scenery—especially along the Rhine. At one station he watched prisoners waiting to be sent to Siberia, remarking simply, “poor devils!”. Families made the journey too. William and Mary Jane Lewis lived in Hughesovka for fifteen years (1880–95) and travelled back and forth five times, a reminder that the route—arduous as it was—became a well‑trodden corridor between South Wales and the steppe.