The biographies of this mother and daughter duo give unique insight into what it was like to live in and around Hughesovka 20 years apart. While Mary Clark’s childhood and early adult life in the town describes a thriving, plentiful land with peaceful hot summers filled with good food and good company, her daughter’s reminiscences tell a vastly different story.

Mary Clark née Penkova

Mary Penkova was born in Hughesovka in 1890 to Valerian Pen’kov (Russian) and Sabina Lange (German). Valerian died of Typhus at 29 years old, leaving Sabina with Mary and her younger sister (whom at the time was only 9 weeks old and later died of infantile paralysis at 11 months). After her husband and daughter’s deaths Sabina took Mary, and they moved onto her parent’s estate in Hughesovka. At first, they lived in an old house and then moved into a large brick bungalow that was built for them with “6 rooms and a kitchen”.

They kept cows, pigs and poultry and Mary described that “life on the estate was good”. She attended a few small schools in Hughesovka but eventually went to a boarding school in Tula for high school before returning in June 1909, following her graduation. After this she spent a long summer “doing almost nothing at all”. The estate was always buzzing with friends and family, her days were spent playing tennis and football, eating homemade desserts and travelling to the seaside. She eventually began working in an office for the company where she kept all the pay for herself as it cost her nothing to live on the estate. They had a month’s holiday with full pay every year, during which she and her mother would again head to the seaside to stay with friends and relax. She states life was not just good in her home but “everywhere in the south. The soil was rich, the harvests plentiful”.

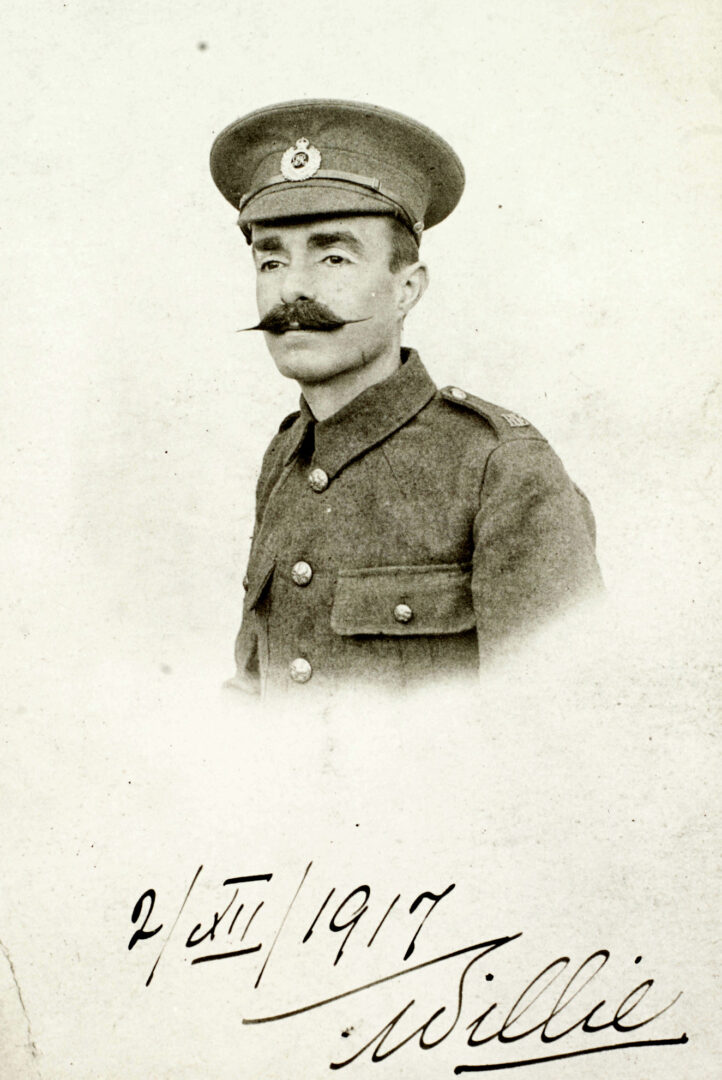

In 1911 the town began having dances once a month from October-March. It was during one of these dances she met her future husband William Clark, who was born in Russia, but had a British father. They were married on the 7th of July 1913. A year later on the 11th of July 1914 their daughter Helen was born.

A month after that in August, war was declared and William signed up and left without even consulting Mary.

Helen Wareing

Following the departure of her father, Helen Wareing née Clark’s early childhood took place during the Russian Civil War and the First World War. She describes immense food shortages, famine and people begging in the street that were “gray-faced and emaciated and could hardly move”. At the age of 7 she began attending school, however after just 1 term a boy in her class referred to her British grandfather as a “bourgeois”, causing a fight. She feared he would have beat her “black and blue” if not for the intervention of a peasant woman. She was homeschooled after this.

The red and white armies constantly warred over Hughesovka, but it was the bandits (deserters of both sides) that were the true danger. All the families’ valuables were buried in their back garden. Bandits would simply walk into their house with guns and take whatever they wanted. Helen recalls how a man once held their maid at gunpoint demanding she give him food, but they had no food to give. She could only look on with horror as her mother Mary begged the man to take anything but please let them live. The winters brought typhus, the family continued to starve.

In 1921 the war finally ended, but this brought a new set of problems. The family was made homeless when the government took over their house to make a club. Housing was limited but eventually they all moved into 1 large room on the ground floor of a house between Hughesovka and Rutchnkovo (a village that is now a suburb of modern Donetsk). They lived here for years until 1925 when William Clark finally returned, a decade after he left! Helen recalls him pulling up to their home well dressed and wearing a hat, she ran inside shouting “Mother, mother, father has come” and then hid under her bed in fear of this strange man who she did not know.

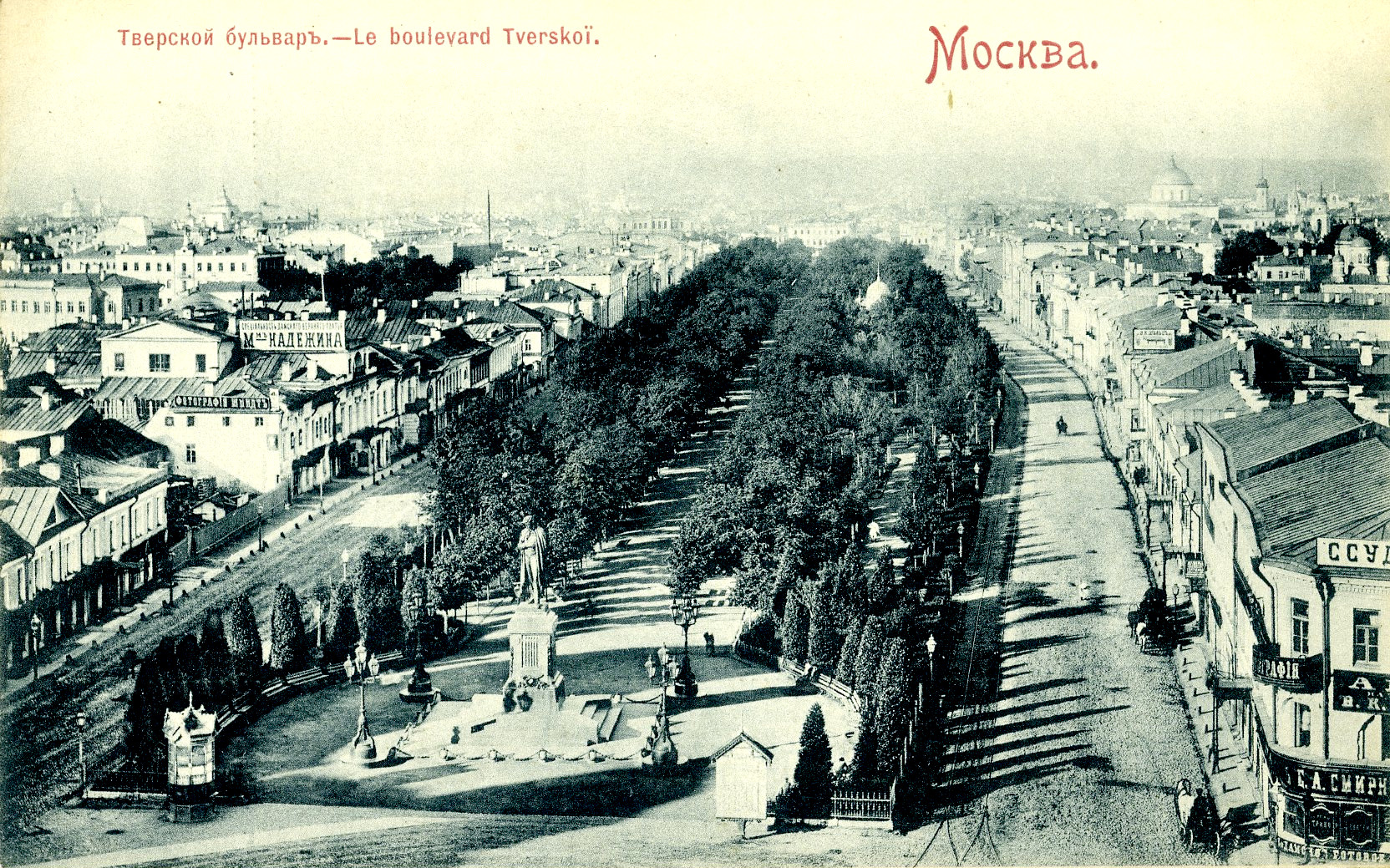

Following the war, William found work in Manchester as an engineer. His company sent him all over Europe, and he jumped at the chance to go to Russia in the hopes of reuniting with his family. After his work in the area was completed his company sent him somewhere new and Mary and Helen moved around with him for the next few years. They lived in Kyrgyzstan, St Petersburg (then named Leningrad), Azerbaidzhan, Ivanovo and then back to Hughesovka for Helen’s last year of schooling. When she graduated her parents and new sibling moved to England, but her Russian education would do her no good there and she did not speak any English. Therefore, at the age of 17 on August 1st, 1931, she moved to Moscow to learn English and work in an office that handled foreign currency and goods.

Moscow during this time was dangerous. Helen’s British heritage and British passport meant she was considered a foreigner and for the 2 years she lived there she did not speak to anyone outside of her relatives (whom she lived with) and the people in her office.

In March 1933 she was away from work for a few days with a cold. When she returned, she found that all the English workers in her office and many of the Russians had disappeared. Fearing for her safety, her colleagues that remained told her to pack a bag and she was taken to a house in the country where she stayed for a few days along with other British workers. When she was finally able to return home, her relatives broke down crying when they saw her. It turned out the people who had vanished had been arrested by the KGB (then known as the OGPU) and were accused of “spying, sabotage and wrecking activities”. When she had not returned home from work, they thought she too had been taken.

Finally, in July 1933 a junior consulting engineer at her office had to return to England to report back to his company and get further instructions and he took her with him. She was thrilled to be reunited with her parents but heartbroken to have had to leave Russia. She finishes her memoirs with this:

‘It took me years to get used to living in England and to the lack of warmth in personal relations. It was only when I came to live in Wales that I felt this warmth again’.